People like to bring order to complexity and locate patterns, especially in the natural world. Think of our biological classification system—do you remember learning mnemonic devices such as “Does King Phillip Come Over for Good Soup?” to learn the taxonomic ranks of Domain, Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, Species? Since the beginning of time, people have identified migration and growth patterns, as well as cyclical patterns throughout the seasons or even between day and night. Humans like order, so classifying landscapes according to patterns of similarities—ecoregions—was inevitable.

What Is an Ecoregion?

An ecoregion is a geographically distinct area that contains similar environmental conditions including physical features like landforms, geology, hydrology, climate as well as soil and biotic (living) features. These conditions influence the types of plants, animals, and habitats that can interact and thrive in that region. The concept of ecoregions is used by ecologists, conservationists, and land managers to better understand and protect biodiversity on a regional basis. This allows for the creation of resilient landscapes that support healthy ecosystems.

There are many ways of classifying ecoregions, and they are typically classified at different scales:

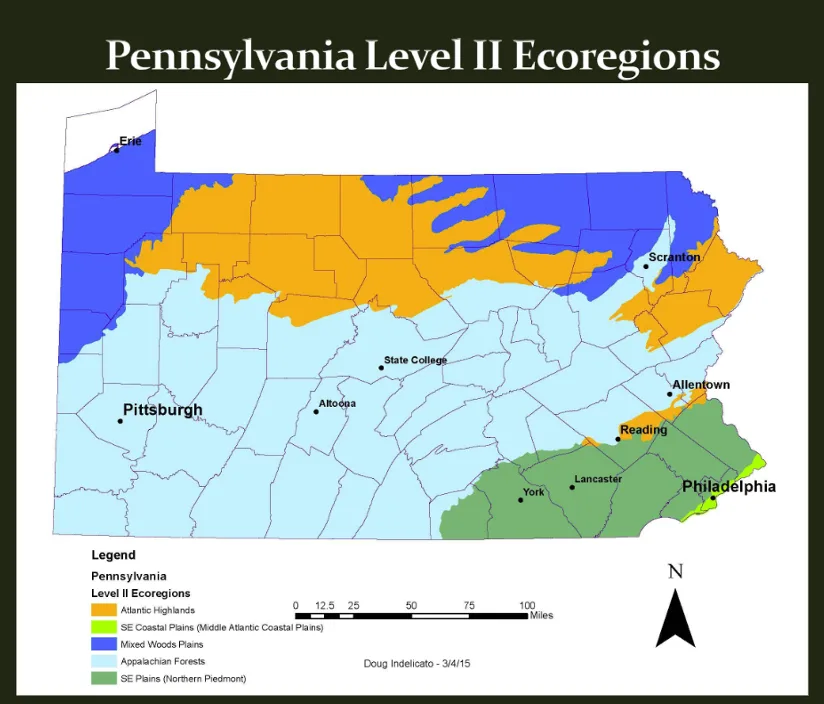

- Level I is broad regions, like the “Eastern Temperate Forests” or “Northern Forests” that cover Pennsylvania.

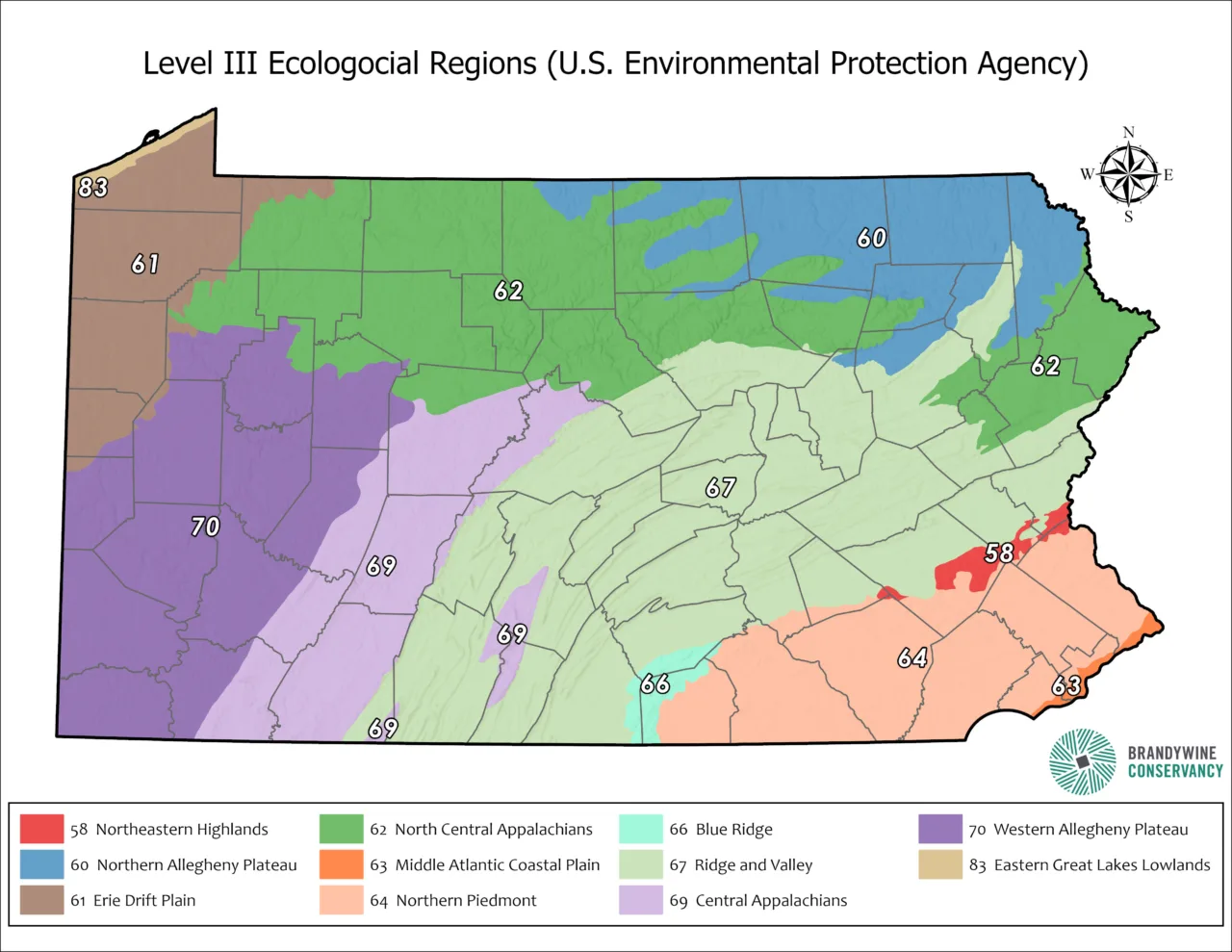

- Level II and III are increasingly detailed subdivisions within Level I and II, respectively, and form up to 11 distinct ecoregions in Pennsylvania.

- Level IV has smaller ecological areas within Level III that allows for specific, localized management, like the Penguin Court Preserve or Brandywine’s Chadds Ford campus.

When creating the Native Garden Hub, Brandywine Conservancy used the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)’s Level III ecoregion classification due to the uniqueness of ecoregions across the Commonwealth. Brandywine Conservancy included ecoregions in the Native Garden Hub to help users understand where specific native plants are most likely to be found and where they should thrive. Plants don’t follow political boundaries, and so limiting a plant’s range to a county or state does not accurately depict their range, which could be affected by human activity and climate change.

Pennsylvania’s Ecoregions: An Overview

Located in the northeastern United States, the majority of Pennsylvania lies within the “Eastern Temperate Forests” Level I ecoregion, while the Pennsylvania Wilds and Poconos & Endless Mountains lie within the “Northern Forests” Level I ecoregion. Eastern Temperate Forests are known for their deciduous trees, seasonal climate, and rich biodiversity while Northern Forests feature cold-tolerant conifers, cold winters, and more wilderness.

At finer scales, such as Level III, Pennsylvania includes multiple distinct ecoregions, each with specific vegetation patterns, geology, and soil types. The EPA recognizes the following Level III ecoregions in Pennsylvania, and this map shows where these ecoregions lie. The numbers are the code assigned to each ecoregion.

1. Blue Ridge (8.4.4)

2. Central Appalachians (8.4.2)

3. Eastern Great Lakes and Hudson Lowlands (8.1.1)

4. Erie Drift Plain (8.1.10)

5. Middle Atlantic Coastal Plain (8.5.1)

6. North Central Appalachians (5.3.3)

7. Northern Appalachian and Atlantic Maritime Highlands (5.3.1)

8. Northern Appalachian Plateau and Uplands (8.1.3)

9. Northern Piedmont (8.3.1)

10. Ridge and Valley (8.4.1)

11. Western Allegheny Plateau (8.4.3)

Each of these regions host distinct ecological communities, driven by differences in elevation, precipitation, land use, and soil types. Past glaciation is a huge factor in these distinguishing characteristics. Glaciers from the most recent Ice Age did not extend beyond Pennsylvania, and, since they did not cover the whole state, Pennsylvania has soils, plants, and wildlife that recolonized the extremes and pushed in from the edges. Pennsylvania—the Keystone State—is a nexus, linking the southern range of northern habitats with the northern range of southern ones. It even has the eastern edge of some western habitats (think of the Jennings Prairie near Slippery Rock, Butler County, PA). This creates richly diverse ecosystems and brings species not commonly found to the Commonwealth.

Ecoregions and Native Plant Conservation

Understanding ecoregions is essential for choosing native plants for habitat restoration, gardening, or land management. Plants that are ecoregion-appropriate are better adapted to local soils, predators, and weather conditions, and they provide optimal support for local wildlife, including pollinators, birds, and mammals. For example, in the Appalachian Plateau, mountain laurel (Kalmia latifolia)—the state flower of Pennsylvania—is a valuable nectar source for native bees, and it supports at least 34 species of butterflies and moths as a host plant.

Organizations such as the Pennsylvania Native Plant Society and the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (DCNR) promote the use of native plants in landscaping based on ecoregional guidelines. Consider doing the same, and using Brandywine’s Native Garden Hub is a great start.

Conclusion

Ecoregions provide a vital framework for understanding the natural diversity of Pennsylvania. From the northern hardwoods of the Appalachian Forests to the oak-hickory forests of the Ridge and Valley to the various wetland grasses and sedges in the Coastal Plain, each region contains unique plant communities that reflect local geology, climate, and soil, which influence plants, animals and their interactions. Recognizing and respecting these ecological boundaries allows land managers, gardeners, and conservationists to make better decisions that support biodiversity and ecosystem health. As environmental challenges like habitat loss and climate change grow more pressing, the ecoregion model offers a tool for guiding sustainable land use and preserving the natural heritage of Pennsylvania.

Want to read more?

Ecological Regions of North America: Toward a Common Perspective by the Commission for Environmental Cooperation gives a nice overview of Level I ecoregions.